How are youth-led organizations responding to the current crises in the international aid system?

Amid deep funding cuts and increasingly hostile narratives toward migrant and displaced populations, especially in recent months, community-based organizations, particularly those led by youth, have been forced to adapt, resist, and develop new forms of action.

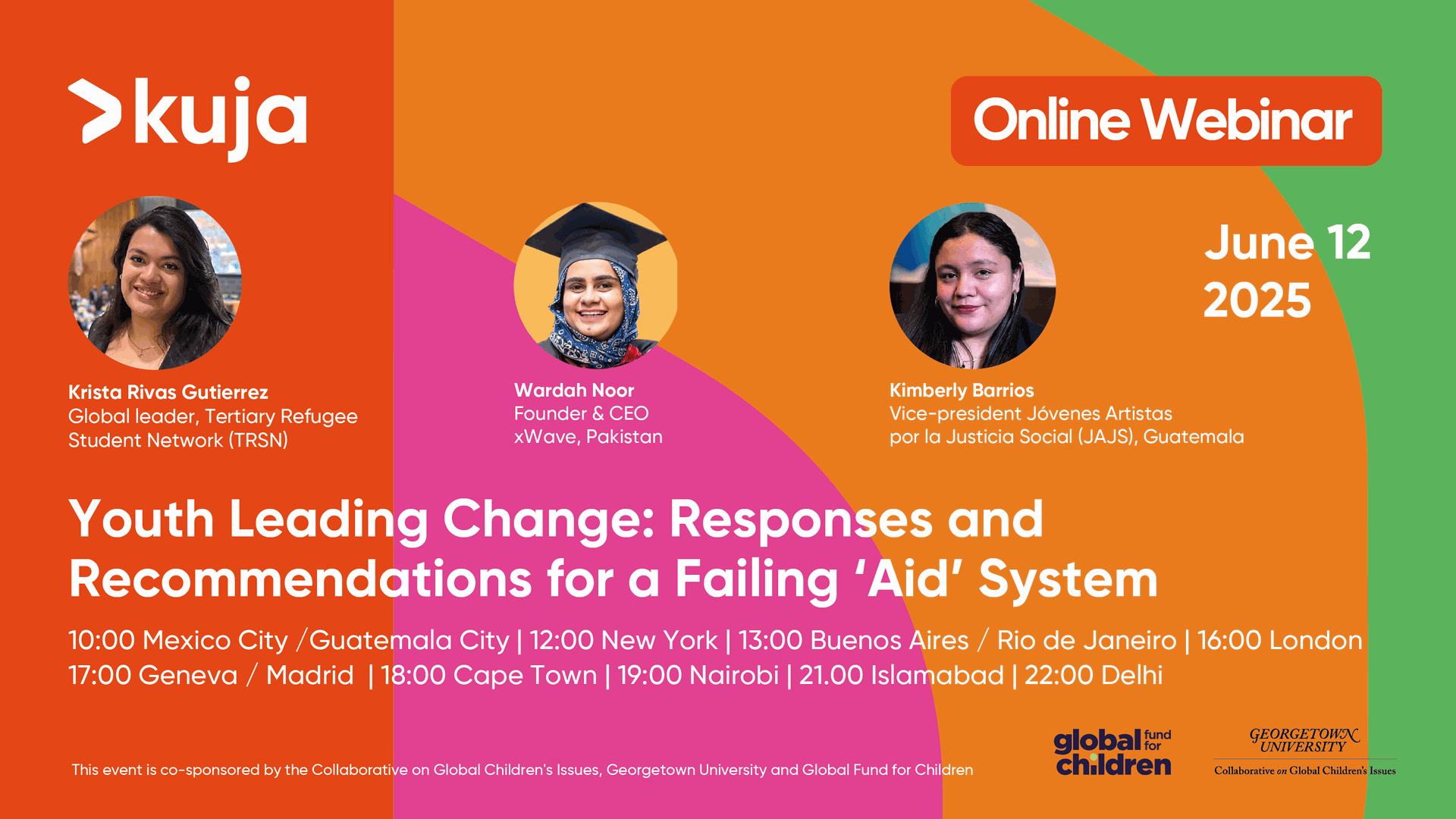

This complex scenario calls for deeper reflection. The webinar Youth Leading Change: Responses and Recommendations for a Failing Aid System, co-sponsored by the Collaborative on Global Children's Issues, Georgetown University and Global Fund for Children, brought together three young leaders to share the strategies and responses of youth-led organizations to the current crises of the "aid" system, focusing on their strengths, lessons learned, and perspectives on the future of aid. This post highlights their insights on advocating for youth rights amid today’s aid crises and provides key recommendations for donors and funders seeking to make a meaningful impact.

Building sustainability from within

Faced with the compounding effects of budget cuts and reduced international support, many youth-led organizations have had to find creative ways to sustain their work. Adopting new models of sustainability, such as entrepreneurship and community-led fundraising, has been crucial in keeping local organizations afloat.

To mitigate the volatility of the current aid system, Wardah Noor, Founder and CEO of xWave Pakistan, emphasizes the importance of reducing dependencies and generating their own revenue. Her team responded to the cuts in funding by launching a service bank and building a revenue engine rooted in community-based entrepreneurship. This approach helped them to continue their local programs and youth mentorship initiatives, even if it meant working with fewer resources and a reduced scope.

Drawing on her experience, she encourages small organizations to develop self-sustaining, revenue-generating systems as a way to cope with the consequences of funding cuts. Beyond being a short-term adaptation strategy, this approach is also an opportunity to prepare for the future. She recommends that funders and INGOs include dedicated support for organizational capacity in their involvement:

"We need to build our capacity to be prepared for crises like these, and the same goes for funders. If organizations need to build that capacity, then funders need to support them. When this crisis is maybe over, or time passes and new perspectives emerge, those grants should have a fixed component where funders dedicate a part of it to building the capacity of the organization—of the founders, the team, or the leadership—so they can respond to such crises. So I think capacity building—and not just capacity building in terms of training, but spending a part of the budget on building capacity for the organization—is needed in the future."

However, to develop these responses, organizations need more flexible grants and trust-based relationships with funders. This way, community-led organizations can make decisions based on their priorities and strengthen their institutions beyond the scope of project funding.

Wardah also invites INGOs and donors to act as connectors, not just funders, by helping open new doors and expanding networks: "They can introduce us to more people who are interested in causes like ours (...) so that youth organizations across the world can keep doing the impactful work they're doing."

The impact of anti-migrant narratives

Another key topic raised during the conversation was the rise of anti-migrant and anti-refugee narratives, and how these increasingly threaten both the funding and day-to-day operations of youth-led organizations working with migrant, refugee, and host communities.

As Krista Rivas, Global Leader at the Tertiary Refugee Student Network (TRSN), explains, these narratives are having a profound impact on their work: "They deepen the barriers to accessing services and increase mistrust and rejection. In the end, people are exposed to new forms of violence simply for having been forced to leave their country." These discourses not only reinforce discrimination on the ground, but they also start to close the doors to funding, limiting the ability of youth-led initiatives to continue their work.

In the field of education, donors, INGOs, and policymakers must do more to support access to higher education for displaced and refugee youth. As Krista emphasizes, access is not only about entering university—it's about justice, dignity, and future opportunities. Higher education should not be viewed as something isolated, but rather as a pathway to growth, contribution, and long-term inclusion. One of her key recommendations is the development of inclusive policies that recognize migrants as a strategic resource. Higher education can support this by offering real opportunities to displaced youth, benefiting not only individuals but also the host societies.

"Something fundamental to investors, organizations, and everyone who can get involved is that we need a long-term vision. Refugee youth don't study only for themselves—they study to contribute, to lead, to return and rebuild, or to stay and invest in the communities that welcomed them. This is truly an investment with a guaranteed return. But for that to happen, governments and international organizations must stop seeing us as a burden or a statistic and start seeing us for what we are: A strategic resource. We have real potential to support development. No country can grow without investing in its youth—and that includes those of us who were forced to cross a border."

Adultcentrism and the role of youth participation

Adultcentrism is another major challenge. Donors and international NGOs should shift their approach to decision-making, prioritizing meaningful youth leadership and participation—not just during project implementation, but also in the design, budgeting, and policy-setting stages. This shift involves acknowledging the key role young-led organizations play: They are closer to the communities, understand the risks, and are often the first point of contact for those in need.

Kimberly Barrios, VP of Jóvenes Artistas por la Justicia Social (Guatemala), explains that one of the main challenges faced by youth-led organizations is the lack of recognition: Youth are not seen as valid actors in decision-making spaces, despite making up a significant share of the population (around 50% in Guatemala, for instance).

Additionally, many young people feel unrepresented in traditional civil society organizations, which pushes them to create their own forms of organizing. Generational gaps in methodology and culture also pose a challenge. One example is artivism, which, according to Kimberly, is often unrecognized or even criminalized as a legitimate form of expression.

Like Krista, Kimberly emphasizes the importance of being heard: "We don't need donors to impose their ideas when we know our territories and understand our needs. But we can build new processes together, new ways of working, and better ways to support those who need it most."

A call for more flexibility

In the face of political crisis, inequality, forced displacement, and weak local and national government responses, many youth-led organizations have turned to international cooperation. This support has been key to the growth of youth movements. However, as we've seen throughout the year, the international aid and funding landscape is undergoing significant shifts. In this changing context, flexibility becomes increasingly important.

Among the limitations of traditional funding, Kimberly highlights that structured donors (despite their valuable and committed work) often impose rigid conditions, as they fund only specific actions, leaving no room for strategic or flexible use of resources. As a result, youth organizations struggle to prepare for crises, innovate, or respond quickly to changing needs.

She also notes that this rigidity often sidelines topics that are central to young people's lives. In Guatemala, for example, art serves as a key tool for peaceful expression and social transformation, yet it remains undervalued by many major donors.

Another key recommendation is to make the aid system more accessible. Many youth-led initiatives are excluded due to barriers such as English-only applications, legal registration requirements, and complex paperwork. Simpler processes, flexible funding, and support that respects local languages and contexts would make a meaningful difference.

According to Kimberly, a flexible donor not only allows organizations to continue during times of crisis but also supports the development of leadership skills and institutional capacity.

She also advocates for flexible models, which enable organizations to explore diverse activities, such as investing in art, using creative methods, and developing community-based processes outside traditional formats.

"We (youth-led organizations) are learning in new ways—new methods, new ways of teaching… I think it's key for donors to move past the idea that learning has to happen in hotels or conference rooms. It can happen under trees, in communities, in remote areas, where the impact is often greater because people feel at ease in their own spaces. Donors should open their minds. Even if they can't fully change their funding structure, they can still reallocate parts of the budget: To support local trainings, renovate a small school in a rural town, or bring art into those spaces…"

To learn more

Throughout this recap, we've learned from these young leaders who shared their experiences and valuable recommendations to other organizations encountering similar challenges, as well as to those in a position to support their initiatives. To learn more, we invite you to watch the full webinar Youth Leading Change: Responses and Recommendations for a Failing Aid System, here.

Author: Mara Tissera Luna, based on presentations by Krista Rivas Gutierrez, Global leader of the Tertiary Refugee Student Network (TRSN); Wardah Noor, Founder and CEO of xWave Pakistan; and Kimberly Barrios, Vice-President of Jóvenes Artistas por la Justicia Social (JAxJS).